After his first hitch and before WWII, Dad drove a Cab during the Eat Texas Oil Boom.

Dad 15, home on leave with niece, Barbara, and nephew, Gene.

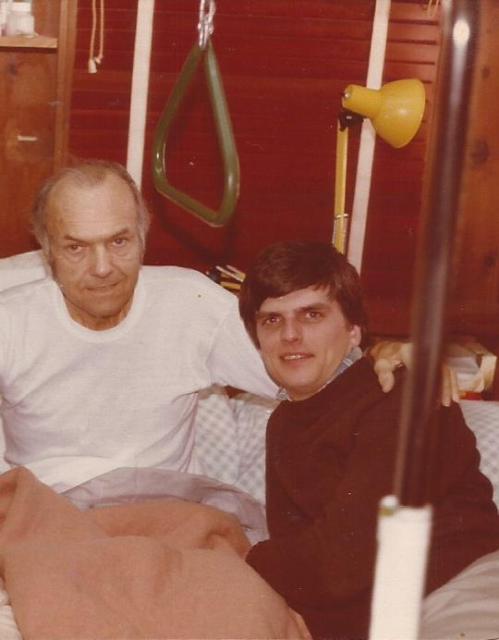

One of my last visits with Dad before he died in 1982., fall of

I have written about fatherhood before in this blog and this mysterious relationship continues to inspire me to understand. One of the wise men talking to Bill Moyers long ago, (Was it Robert Bly or Joseph Campbell or both…?), commented the problem with fathers and sons occurs when they both realize they are in love with the same woman. One of them also spoke about the cultural shift of the 20th century that took men away from real, meaningful work and gave them far more money for far less spiritually rewarding work. This caused their children to see more of their rage than in any previous culture since the barbarians.

Although I might have had better reason than most, I have tried not to see my shortcomings as something caused by my father or anyone else. The mind wants absolutes and yet, there are very few purely good or purely bad people. There are people and they are just all over the place in how and why they make certain decisions. Through the years my brother and friends and even strangers have drifted into long conversations about our fathers. The men who became our fathers grew up in the depression and fought in wars. Poverty and War prepared the men of my father’s era for work and survival and not to be “emotionally present”.

There were a few dads who I thought were terrific, like my grandfather, Raymond Barlow, and some of the men from my church, or Mr. Peppermint, who I wrote about in a previous blog piece, and but they were the exception. My Dad, to put it gently, was not the model of fatherhood portrayed by the stars of the TV shows I watched as a kid. There were fathers on TV like my Dad, but they were the ones played by great character actors as tormented, insecure, prideful, Dads wracked by sorrow, guilt, disappointment or sin. These Dad’s were straightened out and offered salvation by Matt Dillon, Ben Cartwright or Lucas McCain, et al, over the course of an episode. If only life were so neat and tidy.

I was lucky, though. For whatever reason, I had a knack for deterring or distracting my Dad’s grouchiness and quick temper. He was not particularly violent but his demeanor suggested he certainly was capable of it, if you pushed too hard. He was insecure around people who had more education than he had and was a bit of a bully. Like the loyal kid of those rotten, TV-dads, I played the role. Deep down, even as a young child, I had this wiser-than-my-years understanding that my Dad loved me, but that he just had a lot of problems that weren’t my fault. People have told me that I could defuse him with a smile but I remember my fair share of trepidation, quickly judging his mood and, if necessary, heading out the back door, as soon as he got home from a day of selling cars.

I know that things were much harder for my brother, six years older and more sensitive, and our Mom, who seemed to me to do all she could to shield us from Dad’s dark side, though my brother certainly has a different memory. Emotional pain can never be a shared experience. Each person’s experience is so different from another. It is not a knife, or acid, or fire, or a punch to the gut. Yet, we feel cut, poisoned, burned and like the wind has been permanently knocked out of us. Emotional pain gnaws and bores in, and each is left alone to interpret, endure and come out the other side.

So we, my brother and I, have our own story of Dad, and I couldn’t begin to tell his. Our stories are quite different based on the filters of consciousness and memory and the difference in our ages and personality. But, my brother and I both remember the terrifying argument that woke us from our sleep in the fall of 1961. We both remember the gun, laying like an ashtray on the nightstand, and our father’s low, hateful, growl, like an enraged animal, “You can leave, but if you try to take the boys…” and the implied threat of his menacing glance toward the gun. I didn’t remember much at all after that, like a concussion, everything moved slowly, out of focus and in black and white. Then, after the divorce was final, my memory recovered. Life was never really the same and everything, where we lived, how people looked at us, our self-esteem, was shaded by “the divorce”.

So between the divorce, the “Meth”, prescribed for my hyperactivity, and the Kennedy assassination, there were a few years there where I just disappeared into a rich fantasy world. (Also, described in the Mr. Peppermint blog piece) For several years, I saw very little of my Dad. I looked for him, thinking he’d turn up or that he and my mom would reconcile. Once, he gave my mom, my brother and me, a ride when my mom’s car was in the shop. I remember asking my brother, “Are Mommy and Daddy making up?” He looked horrified and, then, sympathetic and said, “No. No they aren’t.”

During this time, I became quite the story teller. A psychologist would say I was crying out for attention but, honestly, I just thought the stories in my head were more interesting and full of possibility than the life I was living. Willie, our once a week domestic worker, would say to me, “Honey-child, are you tellin’ Willie a sto-ree?” Most often, I was. I remember telling her once, that my mom and her parents were discussing a plan to send me to live on a small horse ranch in Missouri, with my Great Aunt Millie and Uncle Homer, because they didn’t have any children.

“ So,” I said to Willie in a grave tone. “ I might not be here when you come next week.”

There was a long pause as Willie ironed. “Oh-Baby, I might not be here next week if you wasn’t here. My heart might break and Jesus just take my soul.” This caused me to backtrack quickly. I loved Willie and she loved me and under no condition could Jesus have her soul. I often “faked sick” on days that Willie was coming so I could stay home and hang out with her. I loved to hear her sing the spirituals while she was ironing. Whenever I told stories to Willie, I felt bad because she seemed to be closer to God than anyone I knew.

“Well, if I don’t go to Missouri, they might send me a horse down here! We could ride it together!”

“Wouldn’t that be fine! Willie and Jeff riding yo’ pony all over town!”

The idea of Willie and me riding a horse together made me laugh so hard I got a stitch in my side. I am so grateful for adults in my life who encouraged my imagination and didn’t judge me too harshly when I was lost and trying to find my way. However, there was one story, and still is, that I would tell, that people most often would assume I was lying about, but was actually true.

In 1933, in East Texas, it must have seemed as though there was no end to the misery. The crash of 1929 had followed an almost decade long “cotton depression”. Share croppers eeked out an existence in the best of years but it had been many years since anything resembling a good year. As poor as they were farm families bonded together in the fields and in church several times a week and helped each other through every hardship. At a time when city people were getting used to having cars, most farm families still used a wagon. While my Dad, whose name was Judson, but was called “J.E.” and “Tiny” as a child and young man and “Jud” later, told what few stories he could recall, in mostly the darkest, saddest, terms. His older sister, Hazel, however, recalled the family as being very poor but not wanting for the most important of comforts, love, family, laughter, warmth and food. Their memories, like mine and my brothers, were separated by some years. The joy my Aunt Hazel could recall was experienced during a time when my Dad was too young to remember. His earliest memory seemed to be when the family was enveloped in tragedy, while Hazel had clear, sweet memories of their mother.

My Dad’s family lived on a farm outside Mt. Vernon, Texas, with a couple of acres to grow food and an additional acreage of cotton to plant, tend, and pick. My Dad was picking cotton by the time he was 8 and working a mule and plow by 11. At the age of 6, his mother died, they believe from blood poisoning, possibly tetanus, as did her infant child, about a month later, of causes unknown.

My grandfather’s mother, who widowed young and raised six children on her own, came to live with the devastated family and care for the children. About a year later, my grandfather, Jesse, found a wife and mother, Oma, for the four children. Oma was 18 and half his age. They met through a friend at church, and Oma was known to possess all of the necessary skills but it turned out badly. Jesse had to run Oma’s relations off from the house once, due to their drinking in the front yard. Jesse’s children had never seen anyone drink alcohol. Oma had terrible mental issues and suffered frequent breakdowns. Her rages could last for several days as she threatened to kill everyone. On more than one occasion the children locked themselves in a bedroom while her husband, Jesse, tried to calm her. When the episodes passed, nothing more was said of them and things returned to as normal a state as possible. The youngest child, Eddie Mae, was sent to live with an aunt, as relatives began to worry for the children’s safety. Somehow the family survived.

By the time he was 14 1/2, my Dad looked like a nearly full grown man. “Tiny” was over six feet tall and had the body of a young man who had dutifully, if not enthusiastically, done a lot of daily farm work. As Hazel tells it in her memoir:

“I remember once, my aunt and uncle and their children were helping us chop cotton. My brother J.E. was standing and leaning on his hoe. My uncle said, “J.E., you will never get rich that way.” J.E. was about ten or eleven years old, but already he was dreaming. He answered, “The only way I’ll ever get rich in a cotton field is to dig up a pot of money; so why work so hard?” J.E. was always dreaming of money and made many of those dreams come true, and, as he always told us, “not in a cotton field!”

In those days between the two great wars, in the years when Mao and Hitler were rising to power, the United States Army enlisted farm boys to work with mule teams. One day, on a trip to town in early 1934, J.E. went to the post office and saw a notice that said the United States Army Cavalry was enlisting “able bodied” men, especially those with experience with work animals, at Ft. Sill, Oklahoma, minimum age, 17. My Dad’s sister, Hazel, against her father’s wishes, had run off and gotten married at 15 and had a baby, “one year and 9 days later”, as she carefully points out. So when my Dad was 14 and headstrong about trying to join the Army, his Dad decided to let him. The family myth was that they were so poor and needed the money that my Dad sent home every month. There may have been some truth in that, but Jesse had, by then, moved the family in close to Sulphur Springs, Texas where he worked a regular job at the Dairy and farmed on the side. Jesse always worked hard to provide for his family, rendering dead animals and repairing water wells. The Depression was hard on everyone but they got by better than when they worked as share croppers. The reality may have been that Jesse knew his son was dreaming of things well beyond life on the farm and the Army might help him grow up a little. Still, there was the matter of J.E. not being old enough to join.

Somehow, my Dad convinced his Dad to write a letter stating that his son, J.E., had been born on a farm, was 17 years old, but didn’t have a birth certificate. My Dad took this letter, some dry food, a little money, a few clothes, and started walking north from Sulphur Springs. He hitched rides on wagons and in cars when he could. The first day, he made it to Paris, Texas, where he had relatives. He lingered a day in Paris, visiting and enjoying the hospitality, and was thrilled to find a ride in a car to Hugo, Oklahoma, leaving Texas for the first time in his life. The driver joked and said maybe Bonnie and Clyde would pick him up. Bonnie and Clyde had been spotted many times in Northeast Texas. They were killed just a few months later, 200 miles to the east in Louisiana.

At that point in his life J.E. had been in a car less than a dozen times and the thrill of cruising over the Red River into another state was not lost on him. Before noon he was walking and hitchhiking west toward Durant. The third night out, somewhere in the hills between Durant and Ardmore there was a heavy dew . The temperature dropped and a cold frost coated the ground. Cold and tired, he sought refuge in a barn. Inside, the barn was almost pitch dark. He stumbled and felt his way to a stack of hay and began to burrow into the warmth when suddenly there was a terrified scream. My dad screamed back. A fellow traveler bolted upright from the haystack, ready to fend off any attack. In the dark, they spoke to each other and realized they were both in the same circumstance. My Dad apologized for startling the stranger so and offered to move on. However, the stranger told my Dad not to worry, there was room in the hay for two, and to make himself comfortable. After walking 20 miles that day and night, Dad slept a deep, long, warm sleep. When he woke, the traveler was already gone.

When he got to Ardmore in the early afternoon, he knew that there were few towns and little on the road between there and Lawton, the city bordering Ft. Sill. The excitement of the trip waned into the sense that he was about 170 miles from home and the gravity of his decision to join the army began to weigh on him. On the edge of Ardmore, he waited, hoping to hitch a ride. Around 3 p.m., a man driving a truck pulled over and Dad asked how far he was going. “Lawton, Oklahoma” was the reply.

The next day, after sleeping at a small rooming house in Lawton, my Dad appeared for induction into the United States Army, almost four months shy of his 15th birthday. The training was rigorous but he was accustomed to hard work and saying,” yes, sir” and “no, sir”, and he quickly became known as a guy who handled the mules and horses with ease. He liked the money he could save and send home. The food wasn’t bad and he enjoyed meeting people from different places and making friends.

Two years later, he had saved a little money. He had routinely sent money home to his family and Jesse shared it with a number of relatives who might have needed some help from time to time, which caused my dad, the guy who didn’t pay child support, to be revered in his family as the guy who helped everyone during the Depression. After two years, he had received a real world education and he had learned to drive. He had also learned was there was a guy named Hitler and eventually the Army would probably have to fight that guy over in Germany. When the papers were delivered for my Dad to re-enlist, he hesitated. He had been corresponding by mail with a cousin and there were opportunities, even during the Depression, in East Texas, mostly created by the Oil Boom. A couple of days later, Dad told his Sargeant, he would not be re-enlisting. The Sargeant was stunned and tried to counsel him on the benefits of service. My Dad was unmoved and, after a couple of stops along the chain of command, he found himself waiting to see the Colonel.

The Colonel was firm and direct. He knew my Dad was a good soldier and could make a good officer. There was still a Depression on out there and that was something Dad should consider. Then my Dad, a two year veteran of the United States Army, 16 ½ years old, said: “Begging the Colonel’s pardon, Sir, but I’m not old enough to be in the Army.” That was pretty much the end of it. They let my Dad leave without trying to correct the record. Dad returned to East Texas but not the cotton fields. As best we can tell he did lots of odd jobs, drove a taxi, bought and sold cars, worked in cafes and nightclubs. Somewhere in there he got married, for the first of six times, had a baby daughter and reentered the Army due to the war. It is unclear to me what the order of events were there

Eventually, he served almost four years in the Philippines and New Guinea. Early in his time there, he met a Filipino boy named Felix. They taught Felix english and he acted as a guide for them. His village also hosted soldiers for wild pig roasts and for awhile they ate food like they had never eaten before. Dad became a Master Sargeant and led convoys of trucks filled with munitions. He admired the brave men he served with and he recalled one who had “jungle rot” on his hands so badly he had to drive and shift the track with only his wrists but never complained. My father was awarded the Bronze Star for keeping the convoys moving while under heavy shelling, and sniper fire. Trucks were hit, exploded and men under his command were killed. There were few real details considering the years he spent there. As most of my friends would agree, the real war stories die with the witness and my Dad held the tradition.

I don’t really know much about my Dad’s youth except the stories that he told us and the stories my Aunt Hazel wrote in her memoir. I am missing the connection to most of his life up until 1965 or so, and that keeps him from being a real person instead of a character with interesting stories. After 1965, I definitely got to know him better but there are still so many holes. Maybe I didn’t ask enough questions. Maybe I missed the content that would bridge his stories to mine and my brother’s. The pain that he created did drive a wedge that we were never quite able to overcome but we worked at it. I am grateful that there are people in his family who thought of him as sort of semi-saint, a great guy with a big heart. I think it was my brother who said, “It’s good to know he was nice to someone.” That was their story with him. I see it in his sister’s memoir and I have heard it in some of my relative’s memories. I know the real truth of my story and while it’s different from theirs, it doesn’t make either story less true.

Very nice. we all have family stories to tell, but you do it with so

much style and grace.

It’s so true that we view our family history through individual filters. It took me a while to realize that my sisters’ recollections and interpretations of certain events weren’t remotely like mine, and that certain memories that were especially painful to them hardly touched me at all. Thank you for this deeply affecting memoir.

Thank you, Marie! I appreciate the encouragement. I am interested in exploring that area between real and imagined memory and the family myth. Hopefully, that interest can be dragged, kicking and screaming, into the braver world of fiction writing. That, I think, offers endless possibilities for story telling. I look forward to sharing more.

I appreciate how you’re able to put yourself into your mindset as a young child and keep in mind the distance between your bother’s and your own perception. Regarding those Depression years in the south, my wife’s father and his brother were placed in an orphanage in east Texas by their mother because she had no way to feed them. Between that experience of abandonment and the stresses of WWII combat in the South Pacific, both ended up with sociopathic tendencies–certainly never able to be caregivers or maintain a relationship–or basic responsibilities such as child support,. As a reader, I’m left with curiosity of your late relationship with your father and whether you, your brother and mother felt stigmatized as divorcees in those little Casa View conformist neighborhoods.